✉️ Good Thought 5

Unifying Your Parts

Welcome to Good Thought, a newsletter about fresh ideas for purposeful living in the 2020s.

I’m Aaron Nesmith-Beck. I founded Atman, one of the first legal psilocybin retreats, and my writing at Freedom & Fulfilment has over 1M pageviews. You can learn more about me here.

If you’re a new reader, you can subscribe below. You can unsubscribe at any time with the link at the bottom of the email.

You can read past issues of Good Thought here.

Unifying Your Parts

Image credit: Sharon Eckstein

“Fuck you!” I say to the empty chair across from me. I sit there for another minute. “Ok,” says my therapist, “switch”. I stand up, take a few steps, turn and sit down in the other chair. “Now, you heard what he just said”, he says, looking at me as I face the chair I was just sitting in, “how do you respond?”

Schizophrenia? No. I’m doing something called the “empty chair technique” in Gestalt therapy. You may have seen this in movies or TV, usually with an imagined person (a parent, for example) sitting in the empty chair. But here, I’m talking to a part of myself.

In the last newsletter I mentioned a framework for understanding the psyche that is among the most fruitful I’ve come across in years. The basic idea is of relating to the psyche as a collection of distinct, mostly autonomous parts. These parts have their own beliefs, desires, intentions, hopes, fears, etc., and act this out in different ways inside our bodies and minds.

Rather than a single, unified agent, the mind is seen as an amalgam of all of its parts. We’ll call this a parts model or parts framework of the mind.

This is a simple but deep idea, and it comes in many flavours. Rather than try to provide a comprehensive overview in this email, I’ll start by highlighting some trustworthy-seeming places I’ve found this idea (I talked about heuristics for gauging trustworthiness in the last email, in case you missed it). Then I’ll describe some implications of adopting a parts model, and some experiments and activities you can try to bring this idea into your own life.

Parts models in Buddhist meditation & TMI

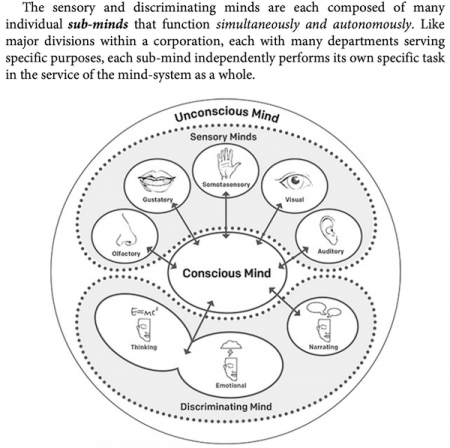

The first parts model I discovered was in the meditation book The Mind Illuminated. TMI describes the mind as composed of sub-minds, each of which have their own tasks and functions, and operate “simultaneously and autonomously”.

Meditation, in this framework, is the practice of aligning the activity of the sub-minds around a particular attentional pattern (e.g. following the breath). In so doing, we unify the activity of the parts, and over time, unify the parts themselves.

TMI was published in 2014, but this model of the mind is based on a much older Buddhist idea. The full TMI model of the mind is actually quite cool, and mildly blew my own mind when I first read it. Each sub-mind is composed of further sub-minds, making the mind fractal-like: parts all the way down to the most basic mental processes. For more here, I’d recommend reading TMI.

Why does TMI, and Buddhism more broadly, seem trustworthy? Because you can verify its claims directly within your own experience. Follow the instruction and notice what happens, and you will see that the theory accurately predicts a series of generalizable phenomenological changes.

Why is it hard to meditate?

A parts model helps explain why it’s hard to stay concentrated during meditation (and equally, why it can be hard to develop and maintain a meditation practice at all). Some parts of you want to meditate. Others don’t. These other parts want to think about work, sex, what you’re having for dinner, the movie you saw last week, what to gift your partner for Christmas, etc.

If five parts of you want to meditate, but another 35 want to do or think about anything else in the cornucopia of exciting, interesting, attention-grabbing things that did, do, or could exist, you’re going to have a hard time sitting down and following your breath.

Parts models in psychotherapy and mental health

Parts models are also common in psychotherapy. Some examples include Internal Family Systems therapy (colloquially called “parts work”), sub-personalities work, and the Gestalt empty chair technique I described above.

Because of my work and interests, I know a lot of therapists. My partner is also a therapist. Anecdotally, therapies based on parts models are quite effective (IFS in particular is popular right now). Personally, I’ve had some really excellent experiences with the empty chair technique, as well as doing parts work on myself.

Psychological ailments make a lot of sense using a parts model. If you’ve ever suffered from an addiction of any kind (food, sex, porn, internet, drugs, alcohol, video games, etc.) then you know how it can feel like a part of you has hijacked the whole system and is running the show, feeding the addiction seemingly against your will. You may also have a part that reacts against the addictive part, feeling shame or disgust towards yourself for succumbing to the addiction.

Parts conflicting around addiction is very intense, but there are many milder forms of conflict between parts too. For example, you’re stuck making a decision and can’t figure out what to do. One part wants one thing, another part wants something else. Or, depending how you construe it, there are coalitions of parts on either side who want different things.

Parts, trauma, and psychedelic therapy

MDMA-assisted psychotherapy is proving to be the most effective treatment for PTSD we have so far discovered. Trauma, including severe trauma like PTSD, also makes sense through a parts model.

A traumatic experience is particularly frightening or painful, and by definition can’t be psychologically processed in the same way as ordinary experience. When a person is traumatized, part(s) are divided or cut off from the rest of the psyche, and get “stuck” in the emotional, psychological, or physiological place the trauma happened. The part is forced out of consciousness because the burden it carries—the unprocessed psychological material associated with the event—is too frightening or painful to be with.

These parts are kept at a distance, in the unconscious, and are generally hard to reach or access. When an experience reminds someone of the traumatic event, the part(s) get “triggered” and the person suddenly re-experiences intense emotions, thoughts, or sensations associated with the trauma.

Research shows that MDMA can help severely traumatized people get into a state where they’re able to readily access their hard-to-reach parts, in order to work with them and integrate them back into the psyche. Therapists working with MDMA explicitly use a parts model (IFS therapy) to heal patients with PTSD.

I saw a video once of an MDMA-assisted psychotherapy patient who had been a turret gunner for the US army in Afghanistan. His PTSD was causing him to blow up in anger and become abusive to his wife and children.

The man described how, during an MDMA session, he was able to travel down into his psyche and find the angry part—a shadow version of himself with red eyes that was kept locked in a cage. He faced the shadow, opened the cage, and embraced the part, beginning the process of freeing it and healing himself. Incredible.

Implications of adopting a parts model

Parts are always trying to help

Importantly, in the parts framework, parts are always well-intentioned. No part is actively trying to harm you, distract you, run you off course, or mess up your life. They are all behaving in ways they genuinely believe will help. Some of these ways are compensatory, or extreme, or may seem incredibly unhelpful to you or your other parts. But from the perspective of parts themselves, they are truly doing what they believe is best.

This means that relating to parts antagonistically tends not to be effectives. Not only does it reinforce divisions in the psyche, but it makes parts resistant to opening up, being understood, and ultimately changing their behaviour.

Imagine you’re working hard on something, doing the best you can in what you believe is a genuinely helpful way. Someone approaches you suddenly, angrily telling you to stop because of all the damage you’re doing. How would you respond?

Now imagine they approach you slowly and first acknowledge all the effort you’re putting in. They take time to genuinely appreciate you, then gently and curiously start to ask you about yourself and your behaviour. That’s how you want to relate to parts.

Why powerful insights can have no effect

A parts model can also explain why powerful insights sometimes have no effect at all on people’s lives. This is unfortunately common with psychedelic experiences, but also happens with ordinary, everyday “aha” moments. The insight happens, feels profound and meaningful, maybe even actionable, and then it’s lost in the sea of other thoughts and experiences and never actualized into reality.

Why does this happen? Because, if the mind is fragmented, only a small number of parts receive/witness/perceive the insight. Then, because these parts aren’t well integrated with the rest of the mind (which is itself divided into many parts), the insight doesn’t propagate widely enough to have any real effect. What is the solution? Further unify the mind!

No more “monkey mind”?

The meditative approach typically teaches that thoughts are a distraction, noise, or mental chatter that ought to be quieted, cleared, or observed and let go of in lieu of paying attention to the meditation object. Thoughts are not thought much of, in most meditative circles.

In a parts framework, by contrast, every single thought you have comes from a part. Thoughts can’t be dismissed as “monkey mind” or a distraction, because they are voiced by a very real part of the psyche that has its own beliefs, intentions, ambitions etc. and that is 100% well-intentioned. This is a completely different perspective from seeing the voices in your head as simple noise or “mental chatter”. Neither is right or wrong, but you’ll get quite different effects depending which you try on.

How to use a parts model for healing and growth

As you may be intuiting, in this model, a more unified mind, with parts that are synergistically relating and collaborative, is preferable to a divided mind, with parts that are in conflict and working against one another.

In broad strokes, a more unified mind means better mental health and overall functioning. The meditative and psychotherapeutic techniques described above are all ways of unifying, reconciling, and integrating parts of the mind.

Adopting a parts framework allows for some interesting and hopefully useful exercises and thought experiments. You can, for example:

- Talk to parts and ask them questions to learn about them, what they believe, and what they want

- Name your parts and start to map out your psyche using this framework. You can see how different parts look, sound, what energy they carry, etc.

- Notice when particular parts tend to show up in your experience, and if there are patterns here (which parts are present for you right now, as you read this?)

Once you get somewhat of a handle on this, you can, for example:

- Notice how your parts react to one another (e.g. one part is activated by an event, and another part allies with it or pushes back against it)

- Have parts talk to one another

- Notice how your parts relate or react to another person’s parts (works best if the other person knows you’re doing this too!)

- Notice very extreme parts, parts that have strong emotions or destructive behaviours associated with them, or parts that seem crazy to you (“I would never do that” etc.)

- Check in with parts that in the past wanted something you now have (e.g. you set a past goal because part(s) of you wanted to reach that goal. How do they feel about it now?)

Further reading on parts frameworks

Parts Work: An Illustrated Guide to Your Inner Life – Excellent introduction to IFS therapy with beautiful illustrations. Highly recommended!

Inner Active Cards – Original source material for the above book. Provides a nice intro and overview of the IFS framework.

Multiagent Models of Mind – In-depth introduction to the parts framework using concepts and language from cognitive science. Rationality-heavy!

Self-Therapy: A Step-By-Step Guide to Creating Wholeness and Healing Your Inner Child Using IFS, A New, Cutting-Edge Psychotherapy – Excellent guide to doing parts work with yourself. Highly recommended!

The Mind Illuminated: A Complete Meditation Guide Integrating Buddhist Wisdom and Brain Science for Greater Mindfulness – Still the GOAT meditation book, in my very humble opinion. Interludes 5 and 7 detail the “Mind-System Model”, TMI’s parts framework.

🕶️ Other cool things

🍄 MDMA SoloInteresting counterpoint to the narrative that psychotherapeutic support is necessary for effective psychedelic healing. I don’t endorse this (and have never actually done MDMA alone, although I’ve heard good things) but it’s certainly thought-provoking. Includes a heavy dose of anti-authoritarianism. My suggestion is to take what you find useful and leave the rest.🏋 So Many Gains, So Little Time: Effective Strength in Minimal Time

HILF (High-intensity, low-frequency) strength training guide my friend Andras put together that received a lot of positive feedback on reddit. After using this approach for ~1.5 years, he was able to max out most of his major lifts (including a 440lb deadlift) without having directly trained the lifts themselves. I have no idea how well this generalizes, but certainly worth a look if you’re interested in strength/bodyweight training.

Thanks for reading Good Thought! If you enjoyed it, why not subscribe?

© 2021 ✉️Good Thought